Welcome to A People's Atlas of Nuclear Colorado

To experience the full richness of the Atlas, please view on desktop.

Navigating the Atlas

You may browse the Atlas by following the curated "paths" of information and interpretation provided by the editors. These paths roughly track the movement of radioactive materials from the earth, into weapons or energy sources, and then into unmanageable waste—along with the environmental, social, technical, and ethical ramifications of these processes. In addition to the stages of the production process, you may view in sequence the positivist, technocratic version of this story, or the often hidden or repressed shadow side to the industrial processing of nuclear materials.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

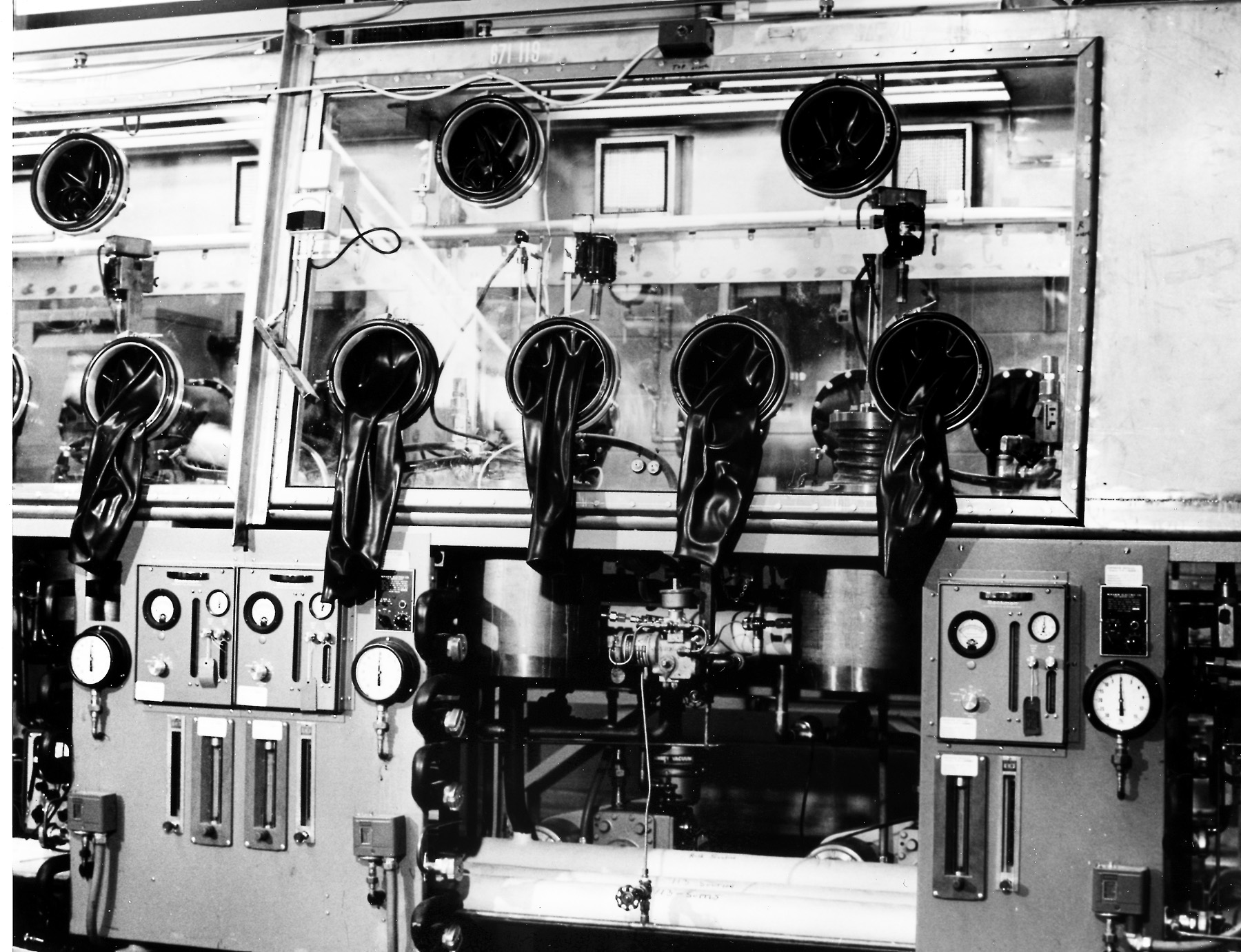

U.S. Department of Energy, A worker operates a glove box, manipulating a figure-eight ingot of plutonium with protective gloves inside an enclosure at Rocky Flats, ca. 1980, Flickr

Essay

The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) considered the production of plutonium bomb triggers for nuclear weapons at the Rocky Flats nuclear facility a critical element of national security. Dorothy Day Ciarlo, “Secrecy and Its Fallout at a Nuclear Weapons Plant: A Study of Rocky Flats Oral Histories,” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 15, no.4 (2009): 347-365.Matching and exceeding the number of nuclear weapons held by the Soviet Union was crucial to a policy of deterrence developed by the United States government in relation to a build-up of nuclear weapons in the USSR during the Cold War. At the Rocky Flats plant, plutonium was handled in specially designed containers made of stainless steel and plexiglass called glove boxes. The glove box was a physical means of protecting workers from the dangers of working with volatile radioactive materials, but it is also a metaphor of the ideal of containment. Maria Rentetzi, “Determining Nuclear Fingerprints: Glove Boxes, Radiation Protection, and the International Atomic Energy Agency,” Endeavor 41, no. 2 (2017): 39-50.The glove boxes were viewed as a technological advance that addressed worker and environmental safety when handling plutonium. Yet in practice, they were an insufficient barrier, undermined by the conflicting directives of the AEC and the Dow Chemical Company (Dow) who prioritized production over safety. The glove boxes are a symbol of how an imperative of national security over public and environmental health created risks rather than addressing them. They also demonstrate how technological barriers are poor substitutes for a systemic lack of oversight, accountability, and transparency for workers, residents, and the environment.

Like other nuclear facilities around the United States, the Rocky Flats plant was owned by the federal government, but operated and managed by contractors. Patricia Buffer, "Rocky Flats History," Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management, 2003, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2020/06/f76/Rocky%20Flats%20History.pdf.Dow managed and operated the plant from 1951 to 1975 for the AEC. The AEC set the requirements for safety and precautionary measures for operations at the plant in order to protect locals, employees, and the environment from accidental radiation emissions. Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999).But they also increased production levels of plutonium in order to ramp up nuclear weapons manufacturing. Safety of workers at the plant, as well as the surrounding residential and urban areas, was compromised repeatedly by lax oversight, justified by the intense production schedules of the AEC and Dow Chemical. As a result of the conditions within the plant, two major fires originated in the glove box rooms of Rocky Flats. U.S. Department of Energy, “The Department of Energy’s Rocky Flats Plant: A Guide to Record Series Useful for Health-Related Research, Volume III, Facilities and Equipment," DOE Openness: Human Radiation Experiments, accessed January 11, 2019, https://ehss.energy.gov/ohre/new/findingaids/epidemiologic/rockyplant/equip/intro.html.

The first occurred on September 11, 1957 in building 771, and the second major fire on the glove box line in buildings 776-777 on May 11, 1969. While these fires were serious, there were over Bruce Campbell, “Past DOE Fires/1969 Rocky Flats Fire," Hughes Associates, Inc., Waybackmachine, archived April 13, 2019, accessed June 28, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20190413194505/http://www.tvsfpe.org/_images/campbell_-_past_fires.pdf.600 reported fires from 1955 to 1971, showing a systemic issue with the storage of plutonium. Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).Throughout this time period, the AEC continued to deny any issues or dangerous releases, and assured the public that there was no danger from the plant.

The fires that began in the glove boxes of Rocky Flats were the result of a purposeful trade-off made by the AEC, Dow, and plant owners and managers who prioritized the production of nuclear materials over safety considerations; local communities and environments were seen as sacrificial in the name of national security. Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).The corrosive secrecy that resulted from national security imperatives led to the compartmentalization of risks and lack of acknowledgement of fires as an inevitable outcome from storing increasingly large amounts of plutonium on-site in the glove box buildings. The glove boxes are also indicative of the gaps left in the federal/private organization of nuclear production, where the federal government gave contracts to private corporations but did not hold them accountable for risk management as long as production quotas were met. Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999).There was no reward for paying attention to safety concerns, unlike the massive bonuses granted by the AEC to private contractors like Dow for producing fissile material on schedule. Additionally, the lack of planning or information for community planners, as well as the secrecy surrounding the plant, meant that few people outside of the AEC and Dow were aware of, or able to plan for, radioactive emissions from fires at the plant.

Organizational and logistical factors also contributed to a systemic lack of investment in worker safety, even after repeated evidence that the Rocky Flats plant was ill-prepared for the specialized risks that an increase of store of plutonium presented. The glove boxes were one layer of security from radiation, but pressure to produce overrode installation and implementation of fire suppression systems. Production schedules took precedence over systems maintenance, such as cleaning vents regularly to prevent buildup that would increase the spread of fires. Alarms were shut off if they interfered with the production of plutonium pits, and large amounts of plutonium-laced waste materials stored in the glove box areas led to a dangerous accumulation of plutonium that could lead to a criticality event. The glove boxes became the only barrier protecting workers, creating complacency around security measures even as more dangerous conditions were created. Despite the 1957 fire, worker safety and radiation protections were seen as impediments to national security, paving the way for the Mother’s Day fire in 1969. Rocky Flats management only reported to the AEC, and Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999).the AEC faced little Congressional oversight, allowing the AEC to self-report (or not report at all) on the severity of radiation releases. Safety and management of waste products from tools like glove boxes were seen as afterthoughts, secondary to the production of the plutonium pits themselves.

An additional complicating factor that led to complacency and systemically dangerous conditions was local support for the plant as an economic driver for the region. In 1951, the Rocky Flats Plant was located on the outskirts of Denver, then a sleepy city on the edge of the Rockies. Ensuing decades saw the exponential growth of the city, and the plant itself drew workers to the region, creating a housing boom around Rocky Flats. Not just the national government, but also Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).local stakeholders were supportive of the plant, and willing to trust AEC and Dow claims of safety at the site. Therefore, multiple stakeholders were invested in a rhetoric that minimized risks from the plant, which employed over 3,000 workers. Most employees were reluctant to raise any concerns as Rocky Flats supplied well-paying jobs, and Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999; Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2013).they believed they were serving a patriotic duty for the country by working at Rocky Flats.

In the vicinity around Rocky Flats, a dependence on the plant for jobs and economic security provided an incentive for local residents, businesses, politicians, and even reporters to trust the AEC’s claims of safety and overlook accidents. Beyond the plant, Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).real estate developers, local businesses, and politicians saw the plant as a point of patriotic pride and economic development for the region and were willing to overlook any environmental contamination that the AEC claimed was negligible or non-existent. Because radiation is invisible, odorless, and tasteless, the claims of authority rested with the AEC and Dow. The local economy came to rely heavily on Rocky Flats, and technologies like the glove boxes were seen as evidence that safety issues were taken seriously, even as less visible systems, such as ventilation and plutonium storage, were ignored.

The glove boxes of Rocky Flats demonstrate the deep ironies that continue to shape the landscape and health of communities around the plant. After the 1969 fire, the public became less complacent in trusting information from the AEC. The fire stimulated public interest, concern, and finally outrage as P.W. Krey and E.P. Hardy, "Plutonium in Soil Around the Rocky Flats Plant," U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Health and Safety Laboratory, HASL-235, August 1, 1970, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/4071339.independent tests of soil and human bodies confirmed that plutonium releases had occurred from other sources, including the 1957 fire and storage of plutonium on-site. The glove boxes became a symbol of both the over-confidence of managers at Rocky Flats in their ability to contain the dangers of plutonium, and their lack of understanding and concern for the specific risks that plutonium presented. The glove boxes stand as a testament to technological hubris in containing the threat of radiation, and a systemic disregard for the safety of workers, the public, and the environment. While the Cold War is ostensibly over, the legacy of nuclear waste in local environments and bodies will continue for generations.

Buffer, Patricia "Rocky Flats History." Department of Energy, 2003. Accessed January 12, 2023.

Campbell, Bruce. “Past DOE Fires/1969 Rocky Flats Fire." Hughes Associates, Inc. Waybackmachine archived April 13, 2019. Accessed June 28, 2021.

Ciarlo, Dorothy Day. “Secrecy and Its Fallout at a Nuclear Weapons Plant: A Study of Rocky Flats Oral Histories.” Peace and Conflict 15, no. 4 (2009): 347-365.

Iverson, Kristen. Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats. New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2013.

Krey, P.W. and E.P. Hardy. "Plutonium in Soil Around the Rocky Flats Plant." U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Health and Safety Laboratory, HASL-235. August 1, 1970. Accessed July 30, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy. “The Department of Energy’s Rocky Flats Plant: A Guide to Record Series Useful for Health-Related Research, Volume III, Facilities and Equipment." DOE Openness: Human Radiation Experiments. Accessed January 11, 2019.

U.S. Department of Energy. “Rocky Flats History.” Accessed January 12, 2023.

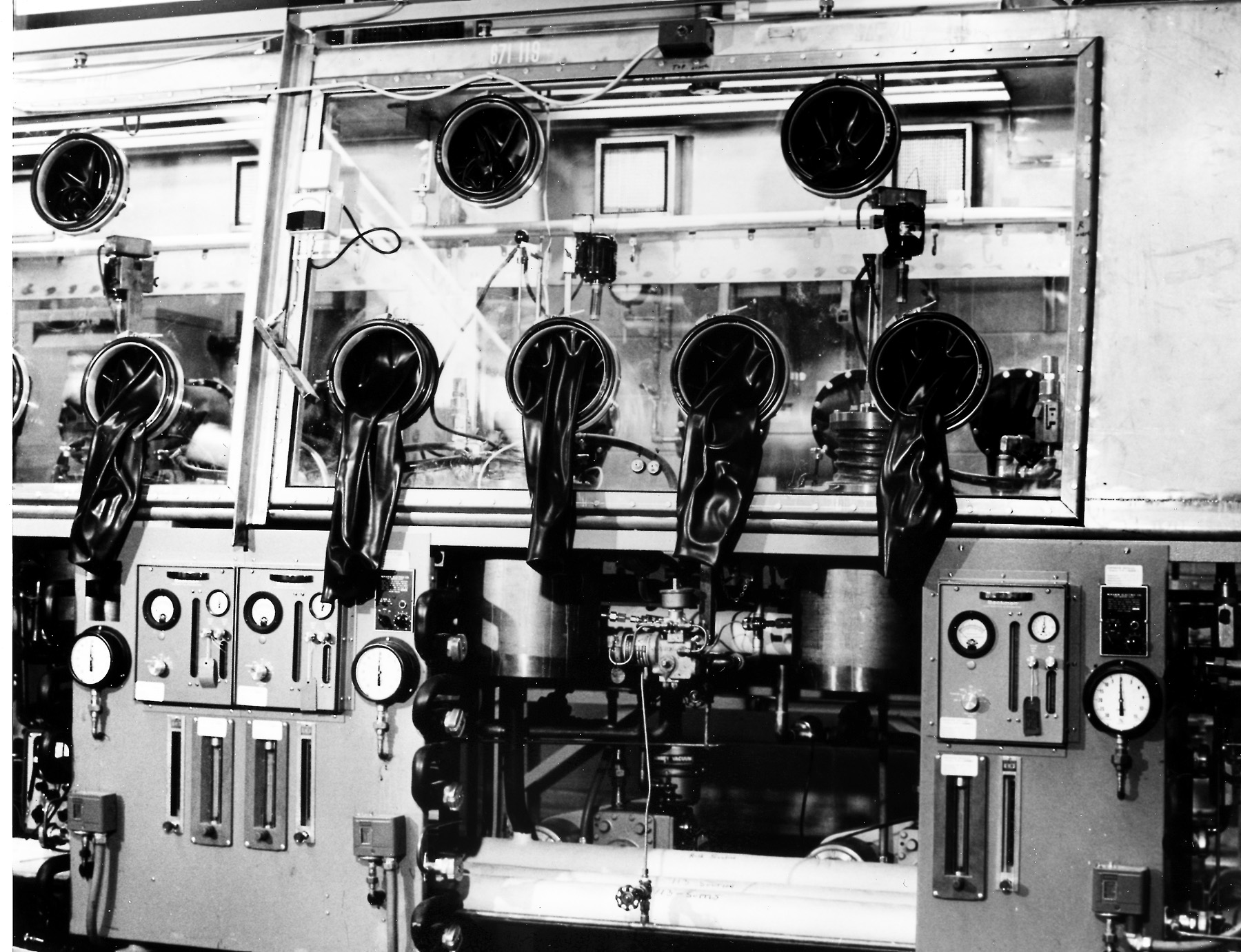

U.S. Department of Energy, A glove box destroyed by the 1969 fire at Rocky Flats, 1969, Wikimedia Commons

Like other nuclear facilities around the United States, the Rocky Flats plant was owned by the federal government, but operated and managed by contractors. Patricia Buffer, "Rocky Flats History," Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management, 2003, https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2020/06/f76/Rocky%20Flats%20History.pdf.Dow managed and operated the plant from 1951 to 1975 for the AEC. The AEC set the requirements for safety and precautionary measures for operations at the plant in order to protect locals, employees, and the environment from accidental radiation emissions. Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999).But they also increased production levels of plutonium in order to ramp up nuclear weapons manufacturing. Safety of workers at the plant, as well as the surrounding residential and urban areas, was compromised repeatedly by lax oversight, justified by the intense production schedules of the AEC and Dow Chemical. As a result of the conditions within the plant, two major fires originated in the glove box rooms of Rocky Flats. U.S. Department of Energy, “The Department of Energy’s Rocky Flats Plant: A Guide to Record Series Useful for Health-Related Research, Volume III, Facilities and Equipment," DOE Openness: Human Radiation Experiments, accessed January 11, 2019, https://ehss.energy.gov/ohre/new/findingaids/epidemiologic/rockyplant/equip/intro.html.

The first occurred on September 11, 1957 in building 771, and the second major fire on the glove box line in buildings 776-777 on May 11, 1969. While these fires were serious, there were over Bruce Campbell, “Past DOE Fires/1969 Rocky Flats Fire," Hughes Associates, Inc., Waybackmachine, archived April 13, 2019, accessed June 28, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20190413194505/http://www.tvsfpe.org/_images/campbell_-_past_fires.pdf.600 reported fires from 1955 to 1971, showing a systemic issue with the storage of plutonium. Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).Throughout this time period, the AEC continued to deny any issues or dangerous releases, and assured the public that there was no danger from the plant.

The fires that began in the glove boxes of Rocky Flats were the result of a purposeful trade-off made by the AEC, Dow, and plant owners and managers who prioritized the production of nuclear materials over safety considerations; local communities and environments were seen as sacrificial in the name of national security. Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).The corrosive secrecy that resulted from national security imperatives led to the compartmentalization of risks and lack of acknowledgement of fires as an inevitable outcome from storing increasingly large amounts of plutonium on-site in the glove box buildings. The glove boxes are also indicative of the gaps left in the federal/private organization of nuclear production, where the federal government gave contracts to private corporations but did not hold them accountable for risk management as long as production quotas were met. Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999).There was no reward for paying attention to safety concerns, unlike the massive bonuses granted by the AEC to private contractors like Dow for producing fissile material on schedule. Additionally, the lack of planning or information for community planners, as well as the secrecy surrounding the plant, meant that few people outside of the AEC and Dow were aware of, or able to plan for, radioactive emissions from fires at the plant.

Organizational and logistical factors also contributed to a systemic lack of investment in worker safety, even after repeated evidence that the Rocky Flats plant was ill-prepared for the specialized risks that an increase of store of plutonium presented. The glove boxes were one layer of security from radiation, but pressure to produce overrode installation and implementation of fire suppression systems. Production schedules took precedence over systems maintenance, such as cleaning vents regularly to prevent buildup that would increase the spread of fires. Alarms were shut off if they interfered with the production of plutonium pits, and large amounts of plutonium-laced waste materials stored in the glove box areas led to a dangerous accumulation of plutonium that could lead to a criticality event. The glove boxes became the only barrier protecting workers, creating complacency around security measures even as more dangerous conditions were created. Despite the 1957 fire, worker safety and radiation protections were seen as impediments to national security, paving the way for the Mother’s Day fire in 1969. Rocky Flats management only reported to the AEC, and Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999).the AEC faced little Congressional oversight, allowing the AEC to self-report (or not report at all) on the severity of radiation releases. Safety and management of waste products from tools like glove boxes were seen as afterthoughts, secondary to the production of the plutonium pits themselves.

An additional complicating factor that led to complacency and systemically dangerous conditions was local support for the plant as an economic driver for the region. In 1951, the Rocky Flats Plant was located on the outskirts of Denver, then a sleepy city on the edge of the Rockies. Ensuing decades saw the exponential growth of the city, and the plant itself drew workers to the region, creating a housing boom around Rocky Flats. Not just the national government, but also Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).local stakeholders were supportive of the plant, and willing to trust AEC and Dow claims of safety at the site. Therefore, multiple stakeholders were invested in a rhetoric that minimized risks from the plant, which employed over 3,000 workers. Most employees were reluctant to raise any concerns as Rocky Flats supplied well-paying jobs, and Len Ackland, Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999; Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2013).they believed they were serving a patriotic duty for the country by working at Rocky Flats.

In the vicinity around Rocky Flats, a dependence on the plant for jobs and economic security provided an incentive for local residents, businesses, politicians, and even reporters to trust the AEC’s claims of safety and overlook accidents. Beyond the plant, Kristen Iversen, Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Shadow of Rocky Flats (New York: Random House, 2013).real estate developers, local businesses, and politicians saw the plant as a point of patriotic pride and economic development for the region and were willing to overlook any environmental contamination that the AEC claimed was negligible or non-existent. Because radiation is invisible, odorless, and tasteless, the claims of authority rested with the AEC and Dow. The local economy came to rely heavily on Rocky Flats, and technologies like the glove boxes were seen as evidence that safety issues were taken seriously, even as less visible systems, such as ventilation and plutonium storage, were ignored.

The glove boxes of Rocky Flats demonstrate the deep ironies that continue to shape the landscape and health of communities around the plant. After the 1969 fire, the public became less complacent in trusting information from the AEC. The fire stimulated public interest, concern, and finally outrage as P.W. Krey and E.P. Hardy, "Plutonium in Soil Around the Rocky Flats Plant," U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Health and Safety Laboratory, HASL-235, August 1, 1970, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/4071339.independent tests of soil and human bodies confirmed that plutonium releases had occurred from other sources, including the 1957 fire and storage of plutonium on-site. The glove boxes became a symbol of both the over-confidence of managers at Rocky Flats in their ability to contain the dangers of plutonium, and their lack of understanding and concern for the specific risks that plutonium presented. The glove boxes stand as a testament to technological hubris in containing the threat of radiation, and a systemic disregard for the safety of workers, the public, and the environment. While the Cold War is ostensibly over, the legacy of nuclear waste in local environments and bodies will continue for generations.

Sources

Ackland, Len. Making a Real Killing: Rocky Flats and the Nuclear West. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.Buffer, Patricia "Rocky Flats History." Department of Energy, 2003. Accessed January 12, 2023.

Campbell, Bruce. “Past DOE Fires/1969 Rocky Flats Fire." Hughes Associates, Inc. Waybackmachine archived April 13, 2019. Accessed June 28, 2021.

Ciarlo, Dorothy Day. “Secrecy and Its Fallout at a Nuclear Weapons Plant: A Study of Rocky Flats Oral Histories.” Peace and Conflict 15, no. 4 (2009): 347-365.

Iverson, Kristen. Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats. New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2013.

Krey, P.W. and E.P. Hardy. "Plutonium in Soil Around the Rocky Flats Plant." U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Health and Safety Laboratory, HASL-235. August 1, 1970. Accessed July 30, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy. “The Department of Energy’s Rocky Flats Plant: A Guide to Record Series Useful for Health-Related Research, Volume III, Facilities and Equipment." DOE Openness: Human Radiation Experiments. Accessed January 11, 2019.

U.S. Department of Energy. “Rocky Flats History.” Accessed January 12, 2023.

Continue on "Friction"