Welcome to A People's Atlas of Nuclear Colorado

To experience the full richness of the Atlas, please view on desktop.

Navigating the Atlas

You may browse the Atlas by following the curated "paths" of information and interpretation provided by the editors. These paths roughly track the movement of radioactive materials from the earth, into weapons or energy sources, and then into unmanageable waste—along with the environmental, social, technical, and ethical ramifications of these processes. In addition to the stages of the production process, you may view in sequence the positivist, technocratic version of this story, or the often hidden or repressed shadow side to the industrial processing of nuclear materials.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

TSGT Greg Kobashigawa, Minuteman missile launch silo located at Malmstrom AFB, Montana. Originally published AIRMAN Magazine., 1 August 2000, National Archives and Records Administration

Essay

In early 1961, residents of northeastern Colorado learned their lives were not as far removed from geopolitics as they might have thought. That spring, officials from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers fanned out across the high plains to survey and map hundreds of sites that the U.S. Air Force wanted for their latest Cold War weapon, the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). For the landowners whose property was chosen, the Air Force gave few options. It was either sell or be condemned. This was, they were told, a matter of vital national security. It was their patriotic duty. The Air Force planned to take over a two-acre square plot of land and start digging. Residents could expect a fully operational nuclear tipped missile to be humming under their little piece of the prairie in 18 months. For general background on the Minuteman system, see: Gretchen Heefner, The Missile Next Door: The Minuteman in the American Heartland (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012); John Lonnquest and David Winkler, To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the United States Missile Program (Rock Island, IL: Defense Publishing Services, 1996); Christina Slattery, et al., The Missile Plains: Frontline of America's Cold War—Historic Resource Study, Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, South Dakota (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2003).In Colorado, fifty missiles were spread over nearly 1,000 square acres, part of a larger deployment of 150 missiles based out of Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming.

For rural Coloradans, their lives, their land, and their families had suddenly become the front line in the global Cold War. Here was foreign policy coming to Main Street.

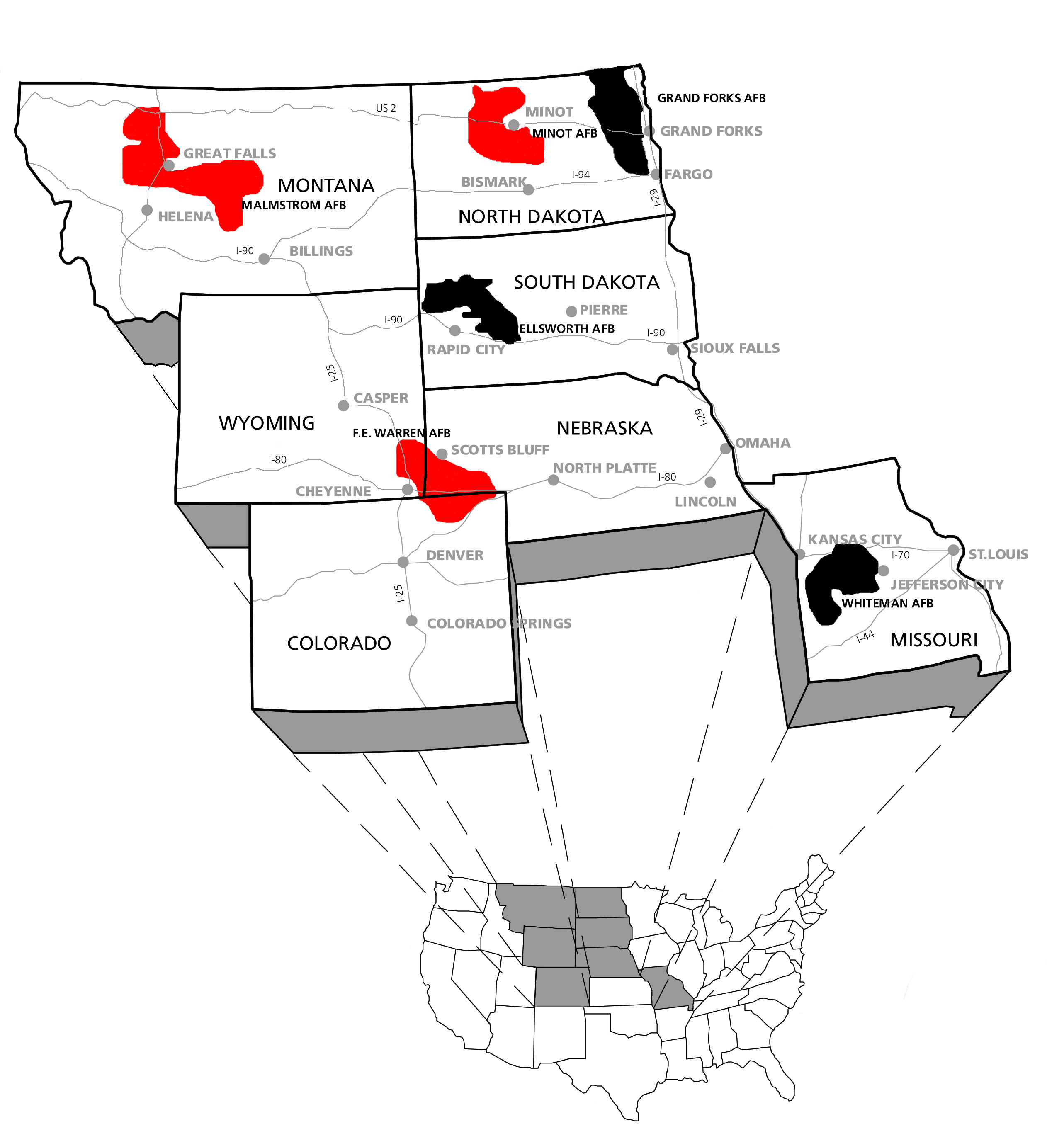

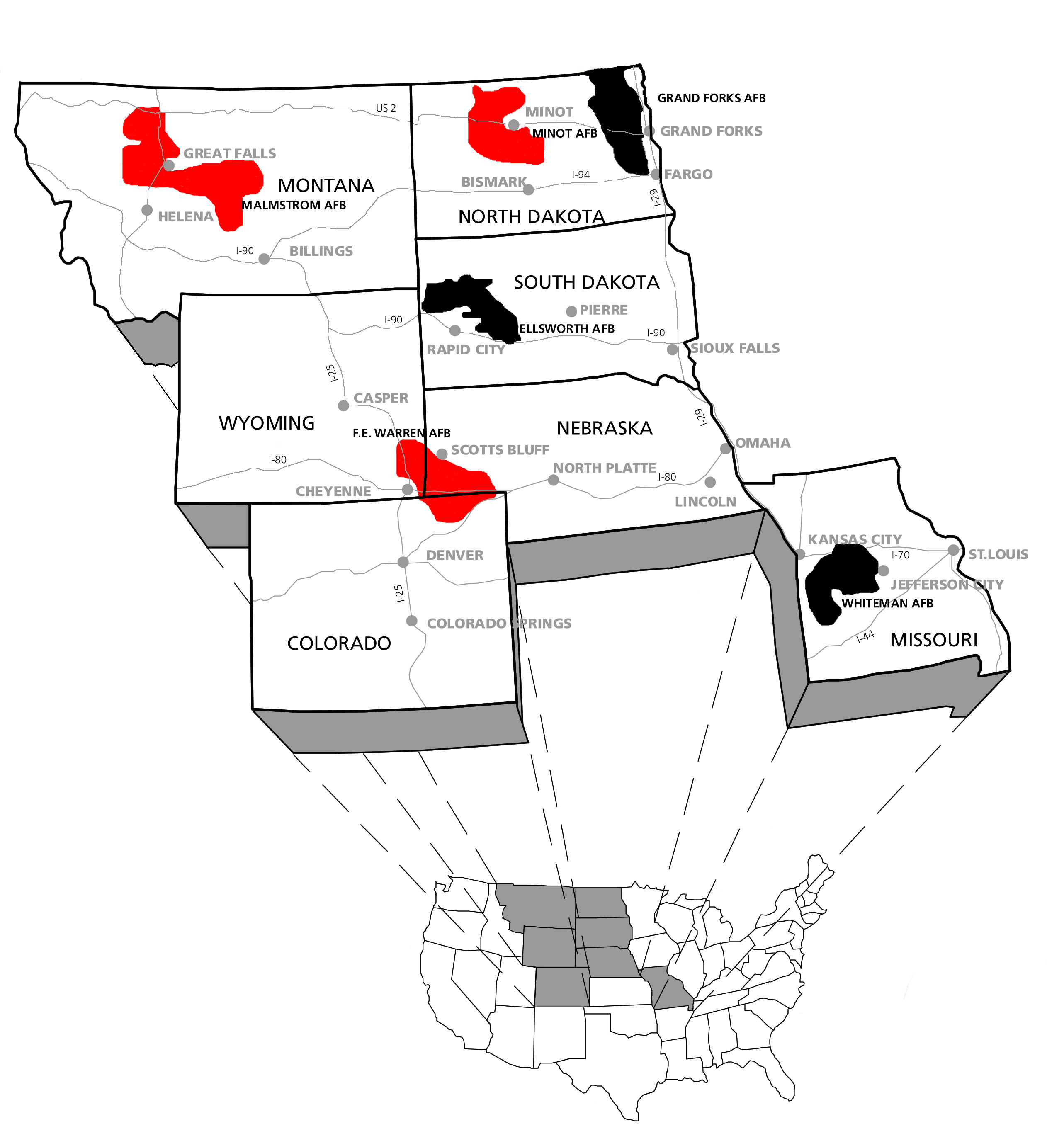

Colorado was not alone in hosting the Minuteman Missiles. Between 1960 and 1968, the U.S. Air Force implanted 1,000 such missiles across the American West, including in Montana, the Dakotas, and Missouri. Each missile location was as invisible as the places where they were deployed. That is because each slender Minuteman rested in a silo that tunneled three stories underground. The only above-ground sign was a 9-foot chain-link fence and a few antennas that poked awkwardly towards the sky. Each silo was topped with a massive, 100-ton concrete lid that would be thrown off in the event of launch. “Push-button warfare,” is what one reporter called it back in the 1960s. The Minuteman also marked the Great Plains with thousands of red bulls eyes since, according to the absurd logic of nuclear deterrence, the Soviet Union would be pointing its missiles at the Minutemen. In the event of war, the missile fields would serve as “sacrificial sponges” meant to soak up enemy warheads and keep them from reigning down on cities and major industrial centers.

This is how many Americans lived the Cold War. Never before had the military permanently implanted its weapons amidst the population and expected life to go on as usual. Nor had Americans ever been asked to be so continually prepared for an invisible and undeclared war.

In fact, the very reasons that so many ranchers loved the high plains—its quiet, away-from-it-all separation—were the very reasons it was considered an ideal place for ICBMs. Far to the north and well inland, these areas were in striking distance of the Soviet Union, yet impossible to reach via an air assault. Moreover, pre-existing military facilities—in this case Wyoming's Warren Air Force Base—made deployment more efficient. Coloradans were also generally friendly to Cold War military needs. A wing of Atlas and Titan ICBMs had already been deployed in the state. The Air Force Academy was establishing ties to the region. In general, then, people in the Colorado missile fields welcomed the Air Force and its lumbering trucks; got used to aircrews helicoptering over their fields; and accepted their place in the Cold War. Better to do this, Rancher quoted in Peter T. Kilborn, “Ranchers Wary of Plan to Wreck Missile Silos,” New York Times, August 17, 1992, A12.a South Dakota missile area rancher admitted, than have a son go off and fight in a war.

And so in late 1961, as rural Colorado landowners got used to the idea of living next door to nuclear missiles, construction workers began digging. The missile fields were mapped by faraway strategic planners in offices in Southern California and Virginia, but built by local boys who got jobs with contractors such as Morrison-Knudson Company out of Nebraska, and Denver’s own Meredith Drilling Company. As was the case around the country, defense dollars brought work. Indeed, a spokeswoman at Warren AFB told the Denver Post, Monte Whaley, “Weld’s Missile Site Park Stirs Echoes of Cold War,” The Denver Post, June 12, 2010; on the Meredith Drilling Company, refer to: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, The Federal Engineer, Damsites to Missile Sites: History of the Omaha District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Washington, DC: USACE, 1985), 194.“When we started putting in the missile sites, the community supported it because we brought in jobs.”

The Meredith Company utilized local knowledge and expertise to excavate the deep holes for the missile silos. They quickly discovered that the methods used to construct silos in North Dakota and Montana would not work in the silty and sandy loam of the Colorado missile fields. So they came up with their own way. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, The Federal Engineer, Damsites to Missile Sites: History of the Omaha District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Washington, DC: USACE, 1985), 194; John Lonnquest and David Winkler, To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the United States Missile Program (Rock Island, IL: Defense Publishing Services, 1996), 442.

The Meredith crews cut open the first 30 feet of earth and then sank a 15-foot diameter shaft 65 feet into each hole. A prefabricated silo was lowered in. The crews averaged drilling out one silo per day between November 1962 and June 1963. Mild winter weather helped.

The project was vast. The Minuteman missile system was designed so that the missiles themselves would be spread across huge areas, each missile a few miles from the next. Ten missile sites were connected by underground cables to a central Launch Control Center (LCC). Colorado hosted five such LCCs and their corresponding missiles. Above ground the LCC looked like a '50s ranch house surrounded by a high, barbed wire fence. Underground was where the high-tech machinery was hidden. Missileers and their launch keys were stationed in egg-shaped capsules buried dozens of feet below the surface. The missileers had with them a sidearm, a shovel, and some provisions in case they got stuck underground due to global Armageddon. They might have to dig themselves out.

Residents of the missile fields quickly adapted to and often embraced the missiles and the air crews that worked there. A Logan County cattle rancher told the Denver Post that she’d Andy Cross, "Cold War-era Silos Still Ready for Battle," The Denver Post, January 13, 2003, https://forums.anandtech.com/threads/cold-war-era-silos-still-ready-for-battle-missile-sites-on-plains-staffed-24-hours-a-day.969316/.“never had a fearful or uneasy feeling about them.” Echoing a common Cold War-era fatalism she insisted that "if a missile ever went off, it would be at its target before we even knew it had been launched.” Of course that also meant that her home would likely be in the crosshairs of a Soviet warhead. But it was easy to overlook such prospects because there were real, everyday benefits to having weapons in your backyard. The Air Force brought better electrification and telephone service. Rural roads were upgraded and maintained to handle heavy trucks and military vehicles. Air crews spent money in small communities.

There were periodic rumors that other things might be spreading out from the missile sites: could the nuclear warheads leak radiation? What about the chemicals used to build the silos? Was the groundwater safe? These were important questions for ranchers whose livelihoods often depended on a thin margin of rainfall.

Toxic chemicals were, indeed, used in constructing the missile sites, a fact that emerged only after some of the missiles were dismantled in the 1990s. During that process the Pentagon, through the Army Corps of Engineers, was mandated to conduct an Environmental Impact Survey for each site. The resulting documents describe underground caches of asbestos, lead paint, sodium chromate liquid, PCBs, chromium, mercury, and cadmium electroplating. The Army Corps of Engineers officers responsible for missile site demolition, however, insist that the materials are contained and should not be a problem. Landowners have simply been asked not to dig or plant things near the fences.

Most terrifying of all, of course, has always been the threat of an accident at a missile site. The detonation of a nuclear warhead would spell certain doom. While the Air Force has long downplayed such mishaps, “'Mishap' at Colorado Silo Damaged Nuclear Missile,” The Denver Post, January 22, 2016, https://www.denverpost.com/2016/01/22/mishap-at-colorado-silo-damaged-nuclear-missile/.one occurred in Colorado as recently as May 17, 2014. That morning among the wheat fields and wind turbines, something went wrong at missile site J-07. While the Air Force has refused to explain exactly what happened, we do know that $1.8 million dollars in damage was done to the missile itself. The three airmen working on the site were stripped of duties and certification to work with nuclear materials. The Air Force issued a statement saying there was no risk to the area and that the incident had been resolved.

Assurances aside, some missile field residents have never been completely comfortable living next door to weapons of mass destruction. Protests have punctuated the relative silence in the missile fields. Even in places as seemingly out-of-the-way as Peetz, Colorado, an agricultural community with just a couple of hundred residents. In 1983, Janet Bigler, "Pastor Retiring After 40 Years of Service," Journal-Advocate, June 24, 2016, https://www.journal-advocate.com/2016/06/24/pastor-retiring-after-40-years-of-service/.the Rev. Ed Bigler, pastor of the Peetz United Methodist Church, began leading an annual Good Friday worship service at missile site J-3, about 1.3 miles outside of town. Bigler, along with the leadership of the church, believed that "United Methodist Church, "The World Community: War and Peace," The World Community 165, Book of Discipline, 2016, https://www.umcjustice.org/who-we-are/social-principles-and-resolutions/the-world-community-165/the-world-community-war-and-peace-165-c.the production, possession, or use of nuclear weapons [should] be condemned.” Outsiders, too, came to protest Colorado’s missile fields. The peace organization NukeWatch mapped the missile fields and continue to provide periodic updates to their “Nuclear Heartland” exposé. More dramatically the Reverend Carl Kabat came to N-8 in a clown suit. On the morning of August 6, 2009, Kabat cut through the chain link fence at the missile site, hammered on the large concrete silo lid, and knelt in prayer. Underground, the Minuteman ICBM hummed without interruption. Above ground, sensors triggered alarms 90 miles away at Warren Air Force Base. Military police were dispatched and within the hour Kabat was arrested for trespassing on U.S. Defense Department property. Kieran Nicholson, "Missile-protesting Priest Arrested at Weld Silo," The Denver Post, August 6, 2009, https://www.denverpost.com/2009/08/06/missile-protesting-priest-arrested-at-weld-silo/.“Nuclear bombs,” Kabat wrote, are “a crime against humanity.” His bail was posted at $2,000.

Today the weapons waiting beneath the high plains, including under the Pawnee National Grassland, are the third generation of the Minuteman system. These missiles each have three, independently targeted warheads that can reach the other side of the world in 30 minutes or less. They are scheduled to remain on alert until at least 2030.

Cross, Andy. “Cold War-era Silos Still Ready for Battle.” The Denver Post, January 13, 2003. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Heefner, Gretchen. The Missile Next Door: The Minuteman in the American Heartland. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Kilborn, Peter T. “Ranchers Wary of Plan to Wreck Missile Silos.” New York Times, August 17, 1992. A12.

Lonnquest, John and David Winkler. To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the United States Missile Program. Rock Island, IL: Defense Publishing Services, 1996.

“'Mishap’ at Colorado Silo Damaged Nuclear Missile.” The Denver Post, January 22, 2016. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Nicholson, Kieran. "Missile-protesting Priest Arrested at Weld Silo." The Denver Post, August 6, 2009. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Slattery, Christina, Mary Ebeling, Erin Pogany, Amy R. Squitieri, and Jeffrey A. Engel. The Missile Plains: Frontline of America’s Cold War—Historic Resource Study, Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, South Dakota. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2003.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Federal Engineer, Damsites to Missile Sites: History of the Omaha District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Washington, DC: USACE, 1985. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Whaley, Monte. “Weld’s Missile Site Park Stirs Echoes of Cold War.” The Denver Post, May 5, 2016 [last updated]. Accessed August 3, 2020.

For rural Coloradans, their lives, their land, and their families had suddenly become the front line in the global Cold War. Here was foreign policy coming to Main Street.

Colorado was not alone in hosting the Minuteman Missiles. Between 1960 and 1968, the U.S. Air Force implanted 1,000 such missiles across the American West, including in Montana, the Dakotas, and Missouri. Each missile location was as invisible as the places where they were deployed. That is because each slender Minuteman rested in a silo that tunneled three stories underground. The only above-ground sign was a 9-foot chain-link fence and a few antennas that poked awkwardly towards the sky. Each silo was topped with a massive, 100-ton concrete lid that would be thrown off in the event of launch. “Push-button warfare,” is what one reporter called it back in the 1960s. The Minuteman also marked the Great Plains with thousands of red bulls eyes since, according to the absurd logic of nuclear deterrence, the Soviet Union would be pointing its missiles at the Minutemen. In the event of war, the missile fields would serve as “sacrificial sponges” meant to soak up enemy warheads and keep them from reigning down on cities and major industrial centers.

U.S. Minuteman missile fields, National Park Service

This is how many Americans lived the Cold War. Never before had the military permanently implanted its weapons amidst the population and expected life to go on as usual. Nor had Americans ever been asked to be so continually prepared for an invisible and undeclared war.

In fact, the very reasons that so many ranchers loved the high plains—its quiet, away-from-it-all separation—were the very reasons it was considered an ideal place for ICBMs. Far to the north and well inland, these areas were in striking distance of the Soviet Union, yet impossible to reach via an air assault. Moreover, pre-existing military facilities—in this case Wyoming's Warren Air Force Base—made deployment more efficient. Coloradans were also generally friendly to Cold War military needs. A wing of Atlas and Titan ICBMs had already been deployed in the state. The Air Force Academy was establishing ties to the region. In general, then, people in the Colorado missile fields welcomed the Air Force and its lumbering trucks; got used to aircrews helicoptering over their fields; and accepted their place in the Cold War. Better to do this, Rancher quoted in Peter T. Kilborn, “Ranchers Wary of Plan to Wreck Missile Silos,” New York Times, August 17, 1992, A12.a South Dakota missile area rancher admitted, than have a son go off and fight in a war.

And so in late 1961, as rural Colorado landowners got used to the idea of living next door to nuclear missiles, construction workers began digging. The missile fields were mapped by faraway strategic planners in offices in Southern California and Virginia, but built by local boys who got jobs with contractors such as Morrison-Knudson Company out of Nebraska, and Denver’s own Meredith Drilling Company. As was the case around the country, defense dollars brought work. Indeed, a spokeswoman at Warren AFB told the Denver Post, Monte Whaley, “Weld’s Missile Site Park Stirs Echoes of Cold War,” The Denver Post, June 12, 2010; on the Meredith Drilling Company, refer to: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, The Federal Engineer, Damsites to Missile Sites: History of the Omaha District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Washington, DC: USACE, 1985), 194.“When we started putting in the missile sites, the community supported it because we brought in jobs.”

The Meredith Company utilized local knowledge and expertise to excavate the deep holes for the missile silos. They quickly discovered that the methods used to construct silos in North Dakota and Montana would not work in the silty and sandy loam of the Colorado missile fields. So they came up with their own way. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, The Federal Engineer, Damsites to Missile Sites: History of the Omaha District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Washington, DC: USACE, 1985), 194; John Lonnquest and David Winkler, To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the United States Missile Program (Rock Island, IL: Defense Publishing Services, 1996), 442.

The Meredith crews cut open the first 30 feet of earth and then sank a 15-foot diameter shaft 65 feet into each hole. A prefabricated silo was lowered in. The crews averaged drilling out one silo per day between November 1962 and June 1963. Mild winter weather helped.

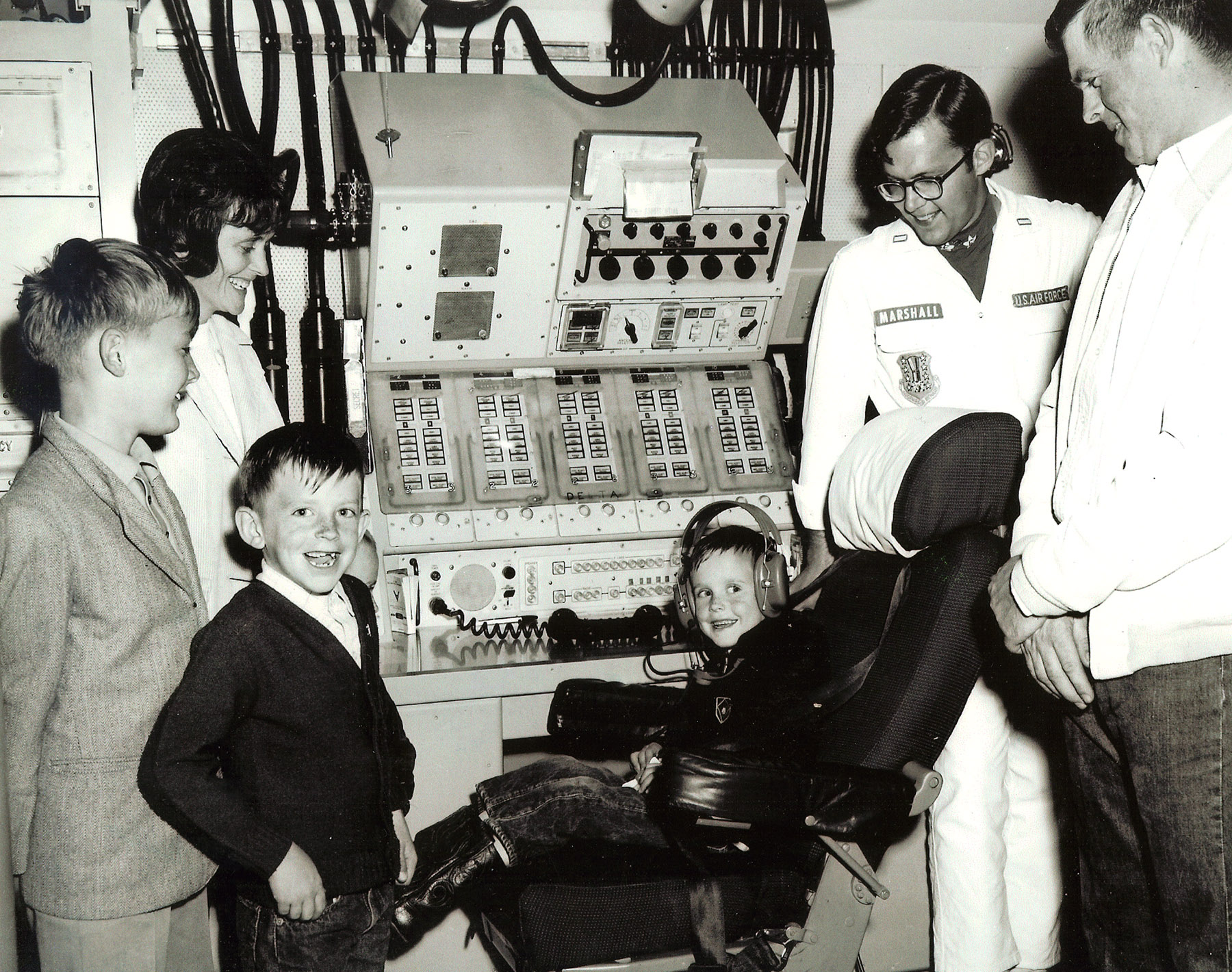

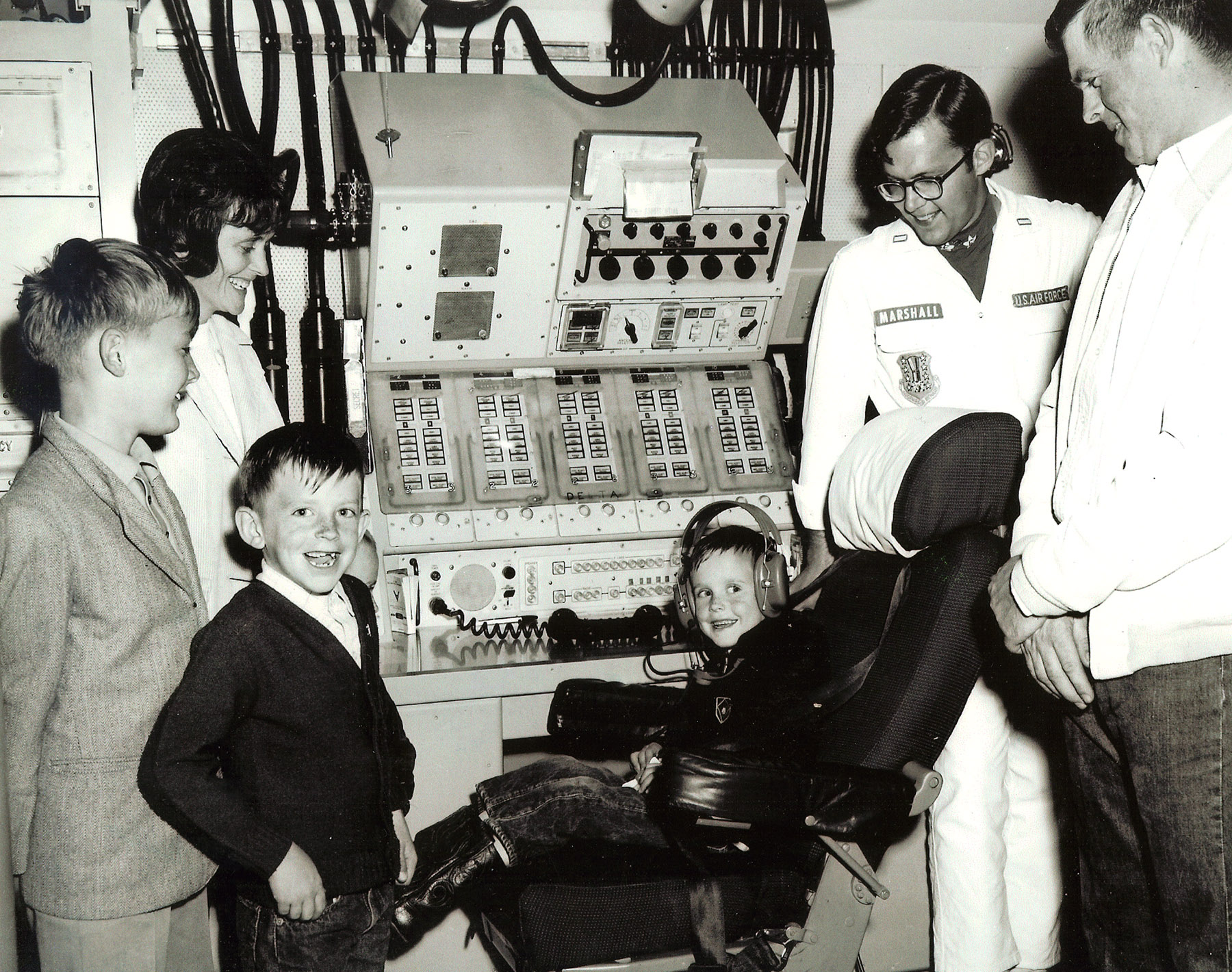

The project was vast. The Minuteman missile system was designed so that the missiles themselves would be spread across huge areas, each missile a few miles from the next. Ten missile sites were connected by underground cables to a central Launch Control Center (LCC). Colorado hosted five such LCCs and their corresponding missiles. Above ground the LCC looked like a '50s ranch house surrounded by a high, barbed wire fence. Underground was where the high-tech machinery was hidden. Missileers and their launch keys were stationed in egg-shaped capsules buried dozens of feet below the surface. The missileers had with them a sidearm, a shovel, and some provisions in case they got stuck underground due to global Armageddon. They might have to dig themselves out.

Residents of the missile fields quickly adapted to and often embraced the missiles and the air crews that worked there. A Logan County cattle rancher told the Denver Post that she’d Andy Cross, "Cold War-era Silos Still Ready for Battle," The Denver Post, January 13, 2003, https://forums.anandtech.com/threads/cold-war-era-silos-still-ready-for-battle-missile-sites-on-plains-staffed-24-hours-a-day.969316/.“never had a fearful or uneasy feeling about them.” Echoing a common Cold War-era fatalism she insisted that "if a missile ever went off, it would be at its target before we even knew it had been launched.” Of course that also meant that her home would likely be in the crosshairs of a Soviet warhead. But it was easy to overlook such prospects because there were real, everyday benefits to having weapons in your backyard. The Air Force brought better electrification and telephone service. Rural roads were upgraded and maintained to handle heavy trucks and military vehicles. Air crews spent money in small communities.

Unknown photographer, A family visits a Minuteman control center in the early 1960s, date unknown, National Park Service

Not everything went smoothly, of course. In 2003, the Denver Post interviewed Dale Schmeeckle of New Raymer (population 120) who complained about the Air Force crews. Over the decades, missile field activities interfered with his dryland wheat farming. Other ranchers throughout the missile fields complained of strange dead spots leaching out from the sites into their fields. The culprit was Andy Cross, "Cold War-era Silos Still Ready for Battle," The Denver Post, January 13, 2003, https://forums.anandtech.com/threads/cold-war-era-silos-still-ready-for-battle-missile-sites-on-plains-staffed-24-hours-a-day.969316/.a sterilant used to kill weeds above the silo.There were periodic rumors that other things might be spreading out from the missile sites: could the nuclear warheads leak radiation? What about the chemicals used to build the silos? Was the groundwater safe? These were important questions for ranchers whose livelihoods often depended on a thin margin of rainfall.

Toxic chemicals were, indeed, used in constructing the missile sites, a fact that emerged only after some of the missiles were dismantled in the 1990s. During that process the Pentagon, through the Army Corps of Engineers, was mandated to conduct an Environmental Impact Survey for each site. The resulting documents describe underground caches of asbestos, lead paint, sodium chromate liquid, PCBs, chromium, mercury, and cadmium electroplating. The Army Corps of Engineers officers responsible for missile site demolition, however, insist that the materials are contained and should not be a problem. Landowners have simply been asked not to dig or plant things near the fences.

Most terrifying of all, of course, has always been the threat of an accident at a missile site. The detonation of a nuclear warhead would spell certain doom. While the Air Force has long downplayed such mishaps, “'Mishap' at Colorado Silo Damaged Nuclear Missile,” The Denver Post, January 22, 2016, https://www.denverpost.com/2016/01/22/mishap-at-colorado-silo-damaged-nuclear-missile/.one occurred in Colorado as recently as May 17, 2014. That morning among the wheat fields and wind turbines, something went wrong at missile site J-07. While the Air Force has refused to explain exactly what happened, we do know that $1.8 million dollars in damage was done to the missile itself. The three airmen working on the site were stripped of duties and certification to work with nuclear materials. The Air Force issued a statement saying there was no risk to the area and that the incident had been resolved.

Assurances aside, some missile field residents have never been completely comfortable living next door to weapons of mass destruction. Protests have punctuated the relative silence in the missile fields. Even in places as seemingly out-of-the-way as Peetz, Colorado, an agricultural community with just a couple of hundred residents. In 1983, Janet Bigler, "Pastor Retiring After 40 Years of Service," Journal-Advocate, June 24, 2016, https://www.journal-advocate.com/2016/06/24/pastor-retiring-after-40-years-of-service/.the Rev. Ed Bigler, pastor of the Peetz United Methodist Church, began leading an annual Good Friday worship service at missile site J-3, about 1.3 miles outside of town. Bigler, along with the leadership of the church, believed that "United Methodist Church, "The World Community: War and Peace," The World Community 165, Book of Discipline, 2016, https://www.umcjustice.org/who-we-are/social-principles-and-resolutions/the-world-community-165/the-world-community-war-and-peace-165-c.the production, possession, or use of nuclear weapons [should] be condemned.” Outsiders, too, came to protest Colorado’s missile fields. The peace organization NukeWatch mapped the missile fields and continue to provide periodic updates to their “Nuclear Heartland” exposé. More dramatically the Reverend Carl Kabat came to N-8 in a clown suit. On the morning of August 6, 2009, Kabat cut through the chain link fence at the missile site, hammered on the large concrete silo lid, and knelt in prayer. Underground, the Minuteman ICBM hummed without interruption. Above ground, sensors triggered alarms 90 miles away at Warren Air Force Base. Military police were dispatched and within the hour Kabat was arrested for trespassing on U.S. Defense Department property. Kieran Nicholson, "Missile-protesting Priest Arrested at Weld Silo," The Denver Post, August 6, 2009, https://www.denverpost.com/2009/08/06/missile-protesting-priest-arrested-at-weld-silo/.“Nuclear bombs,” Kabat wrote, are “a crime against humanity.” His bail was posted at $2,000.

Today the weapons waiting beneath the high plains, including under the Pawnee National Grassland, are the third generation of the Minuteman system. These missiles each have three, independently targeted warheads that can reach the other side of the world in 30 minutes or less. They are scheduled to remain on alert until at least 2030.

Sources

Bigler, Janet. "Pastor Retiring After 40 Years of Service." Journal-Advocate, June 24, 2016. Accessed August 3, 2020.Cross, Andy. “Cold War-era Silos Still Ready for Battle.” The Denver Post, January 13, 2003. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Heefner, Gretchen. The Missile Next Door: The Minuteman in the American Heartland. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Kilborn, Peter T. “Ranchers Wary of Plan to Wreck Missile Silos.” New York Times, August 17, 1992. A12.

Lonnquest, John and David Winkler. To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the United States Missile Program. Rock Island, IL: Defense Publishing Services, 1996.

“'Mishap’ at Colorado Silo Damaged Nuclear Missile.” The Denver Post, January 22, 2016. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Nicholson, Kieran. "Missile-protesting Priest Arrested at Weld Silo." The Denver Post, August 6, 2009. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Slattery, Christina, Mary Ebeling, Erin Pogany, Amy R. Squitieri, and Jeffrey A. Engel. The Missile Plains: Frontline of America’s Cold War—Historic Resource Study, Minuteman Missile National Historic Site, South Dakota. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2003.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Federal Engineer, Damsites to Missile Sites: History of the Omaha District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Washington, DC: USACE, 1985. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Whaley, Monte. “Weld’s Missile Site Park Stirs Echoes of Cold War.” The Denver Post, May 5, 2016 [last updated]. Accessed August 3, 2020.

Continue on "Essays Path"