Welcome to A People's Atlas of Nuclear Colorado

Navigating the Atlas

Using the buttons on the left, you may also browse the Atlas's artworks and scholarly essays, access geolocated material on a map, and learn more about contributors to the project.

If you would like to contribute materials to the Atlas, please reach out to the editors: Sarah Kanouse (s.kanouse at northeastern.edu) and Shiloh Krupar (srk34 at georgetown.edu).

Cover Image by Shanna Merola, "An Invisible Yet Highly Energetic Form of Light," from Nuclear Winter.

Atlas design by Byse.

Funded by grants from Georgetown University and Northeastern University. Initial release September 2021.

Essay

Background: “Atoms for Peace” and “Operation Plowshare”

When people think of nuclear detonations they think of Nevada or New Mexico. They don’t usually think of Colorado. However, other than Nevada, no other state has had as many nuclear bombs detonated on its soil as Colorado. In 1969 and again in 1973 two nuclear bomb-devices were exploded on Colorado’s The Piceance Basin is a geological formation in Northwest Colorado containing reserves of coal, natural gas, and shale.Piceance Basin to determine whether nuclear stimulation (nuclear fracking) of oil-shale deposits would be more efficient and commercially viable than conventional chemical explosives or hydraulic fracturing. The tests were part of the Atoms for Peace Program, initiated by President Eisenhower in 1954 to find peaceful uses for nuclear technologies. The Atoms for Peace program was intended to redeem the image of the U.S. nuclear weapons complex, tarnished by its association with weapons of mass destruction. The peaceful application of nuclear technology would show that Americans could use the power of the atom, as Eisenhower put it: Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Atoms for Peace,” December 8, 1953, United Nations General Assembly, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/dwightdeisenhoweratomsforpeace.html; “Atoms for Peace Speech,” International Atomic Energy Agency website, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.iaea.org/about/history/atoms-for-peace-speech.“to serve the needs rather than the fears of mankind.”The branch of Atoms for Peace that experimented with nuclear explosives was called Operation Plowshare. Plowshare’s mission was to use nuclear bomb technology to engineer titanic-scale excavations in the construction of harbors, inter-ocean canals, trans-mountain highways, deep-geologic “repositories” for nuclear waste and natural gas storage. All Plowshare experiments made such projects worse than useless, however, by rendering them radioactive. This includes the gas from nuclear fracking experiments in Colorado called Project Rulison and Project Rio Blanco, and in New Mexico, Project Gasbuggy (the only other nuclear stimulation experiment by Operation Plowshare, performed in 1967). As a result, Colorado residents allied against the assumed benevolence of nuclear applications, such as nuclear stimulated gas programs, and pushed the state to be first to pass legislation against nuclear detonations without voter approval across the state.

The Blast, the Chimney, and the Buffer Zone

U.S. Department of Energy, Diagram illustrating a hypothetical technique for using the simultaneous detonation of two nuclear devices to stimulate natural gas production, 1967, Flickr

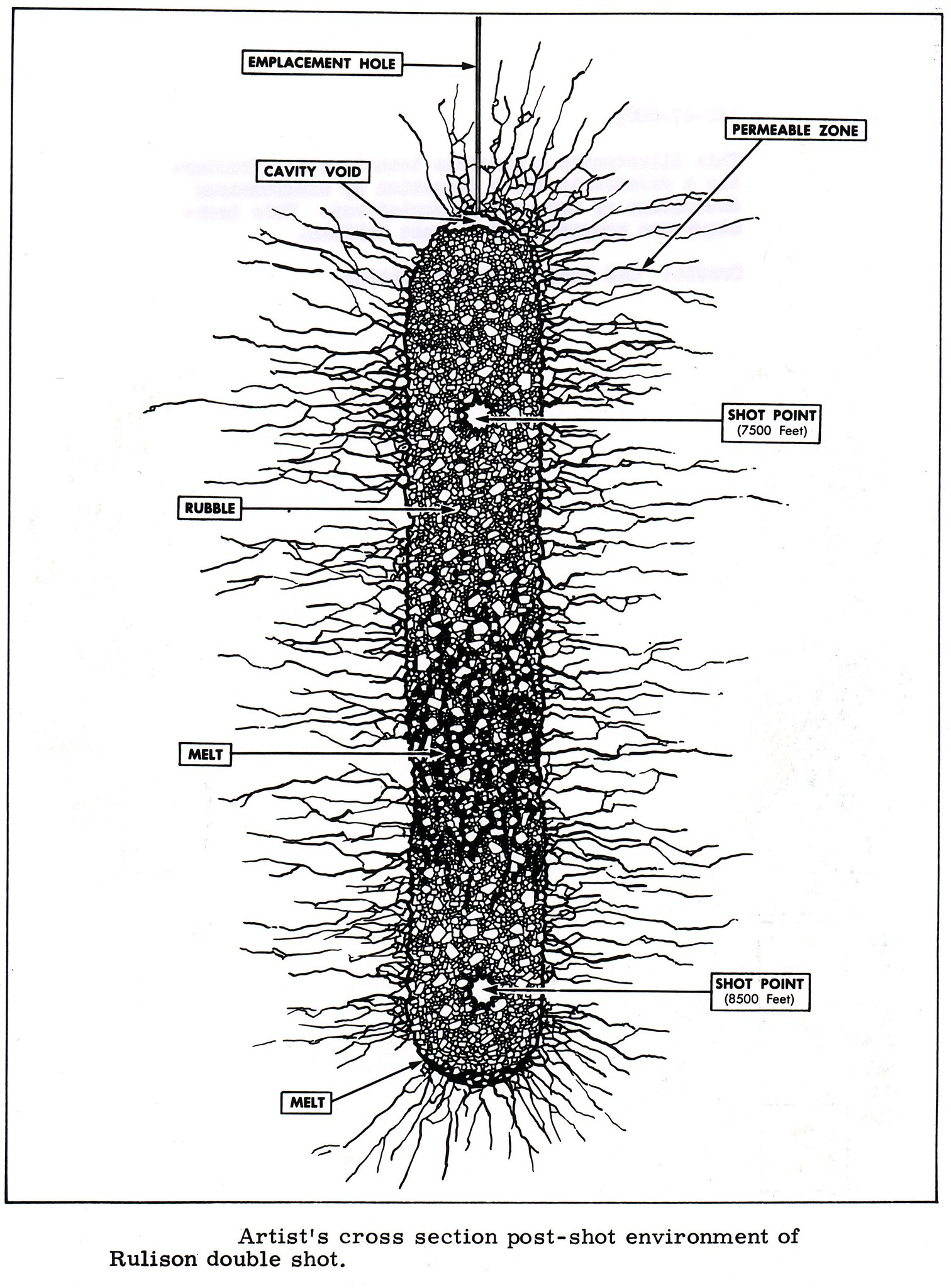

That the Howard A. Tewes, “Survey of Gas Quality Results from Three Gas-well-stimulation Experiments by Nuclear Explosions,” OSTI.gov / U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Scientific and Technical Information, 1979, accessed July 26, 2020, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/6276057.Livermore scientists did not foresee the radiation effects for consumer gas markets is something of a mystery, since the yields of the bomb-devices detonated were not insignificant. The bomb-device used for the Rulison test had a 41-kiloton yield and Rio Blanco’s three devices amounted to 99 kilotons, making Rulison almost three times greater, and Rio Blanco almost seven times greater, in yield than the bomb that devastated Hiroshima. The power, velocity, and impact of even a single 41 kiloton bomb—as at Rulison—is immense. In tens of milliseconds everything around the detonation source deep in the ground is vaporized. In a flash, where once solid rock existed, only a cavity remains. A high-pressure shock wave spreads from the blast, fracturing the rock everywhere behind the cavity wall far out into the shale deposits. The vaporization pressure and temperatures are enormously high at the explosion source, while the nearby rocks that were not vaporized collapse into the cavity and a chimney of rubble forms, filling the chamber with radioactive gas and water. The Rulison chimney had a 78-foot radius with a height estimated at 275 feet. Shear fractures extended to a maximum of approximately 275 feet with a maximum fracturing radius up to 433 feet. The cavity, at the center, was thus surrounded by a zone of highly permeable fractured rock. It is this zone from which gases, water, and kerogen (the basis of shale-oil) flow into the chimney and are drawn up to the surface by means of a separate re-entry well. At both Rulison and Rio Blanco the gas obtained from the re-entry well was duly flared (burned) into the atmosphere, all of it radioactive. At Rulison the power of this fracturing produced 10 times more natural gas than non-nuclear stimulated gas production methods. Combine this quantity with the high quality of the River Formation shale and one can understand why the oil and gas industry has ruthlessly targeted this region.

The Bush/Cheney 2005 Energy Reorganization Act deregulated the oil and gas industry exempting it from federal regulations, such as the Clean Water Act, which protects the U.S. water supply from deadly chemicals including radiological contaminants. The reorganized Energy Act allows the oil and gas industry to use chemical explosives and other polluting agents previously prohibited; neither are they required by law to report what substances they use either in the drilling process or in the wastewater injection process. Because of these changes in the Energy Act, drillers began entering areas to drill that were previously inaccessible to them, such as the Piceance Basin. Suddenly Rulison and Rio Blanco became at risk of being disturbed, making the buffer zone a very contentious issue, and it remains so today.

At the time of the tests in 1969 and 1973 the Department of Energy (DOE) had stipulated a 3-mile buffer zone around each site to keep oil and gas drilling from out of the fracture zone made by nuclear stimulation. Drilling in this area could endanger workers and possibly open pathways to radiation that would potentially contaminate aquifers that feed water wells used by local inhabitants (as has occurred with hydrofracking). Since radioactive contamination has not been found by DOE monitoring over the years, the buffer zone has been reduced repeatedly to accommodate the industry. Most recently the Office of Legacy Management (DOE’s oversight office in the area) has reduced the buffer zone all the way to the 44-acre lot surrounding the blast site, within which drilling is prohibited.

The State of Colorado does not agree with the DOE’s drastic downsizing of the restricted area, nor do local inhabitants who, since the period of the tests, have suffered under the environmental and social impacts of one of the most intense mining booms in recent Colorado history. In compromise, when hydrofracking companies apply to the state for a drilling permit to drill within a 3-mile radius of ground zero, the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC) “notifies DOE and provides an opportunity to comment on the application.” To protect the health of the people of Colorado, an application to drill within the one-half mile zone requires a full hearing before the commission.

The Office of Legacy Management also requires the drilling company to test for radionuclide contamination in the gas and inform it if any is found. All direct monitoring—aside from the yearly surface water testing done by the EPA—is left to the industry to perform. Some oil and gas companies have claimed they aren’t bound by the state but only by the federal government. None have yet attempted to move beyond the half mile exclusion zone, although one Texas company that applied to Legacy Management for an exemption decided to withdraw the application. The public response has been one of anger and of active lobbying to gain more control over their environment and their safety. While citizens have begun to gain more influence over the industry, they’ve not yet been able to stop hydrofracking companies from inching closer and closer to ground zero. Indeed, the Office of Legacy Management encourages frackers to do so.

Radiation Contamination

Historically, the gas generated from each “stimulation” site at Rulison and Rio Blanco proved to be too radioactive for commercial use, and because of radiation contamination, all soil around the surface of the sites and all equipment used for drilling and excavation has had to be removed and trucked to Nevada for burial in rad-waste repositories. At Rio Blanco, radioactive waste-debris was injected into local wells and surface streams such as Fawn Creek, threatening the Green River aquifer, and the prodigious radioactive gas from both tests was flared through large chimney flues extending high above the ground in attempts to release the irradiated gas high up into the atmosphere. Releases lasted for extended periods of time, and residents of the area claim the flares resulted in fallout at surface ground zero and off-site in areas farther afield, requiring extensive clean-up of contaminated soil and equipment. Radiation from flared gas was routinely described by the DOE to be only as bad as the combined total of global fallout from the nuclear arms race—hardly a reassuring statistic.

U.S. Department of Energy, The Project Rulison 40-kiloton nuclear device is lowered into its 8,442-foot deep emplacement hole, August 14, 1969, Flickr

The Rulison explosion was also accompanied by significant “surface venting” of irradiated smoke, dirt, and debris breaking through the surface of the mountain and escaping into the atmosphere even though the underground blast was detonated 8,400 feet below ground surface. It is not technically possible to “clean up” radionuclides from deep underground contamination or deep soil or water contamination. These sites will never be free of long-lasting radionuclides. They will remain a radiological hazard particularly for mining operations, during earthquake events, or during other unforeseen occurrences. The radionuclides of concern at both test sites are Tritium, Krypton-85, and Carbon-14. C-14 is present primarily when attached to methane molecules. All three radionuclides are highly mobile in gas and water, and they are readily absorbed into the bloodstream, potentially causing cancer and other radio-illnesses, particularly to unborn fetuses, children, and women. Tritium is of concern because it is the most abundant radionuclide produced by the fission process; it is also of concern because of its mercurial nature moving easily and quickly between gas and water phases. Tritiated water appears both as liquid water and water vapor and it is also present as tritiated methane.

The DOE/Legacy Management’s document titled “The Rulison Path Forward” argues that the Rulison site is safe to allow fracking up to the 40-acre ground zero zone. This assessment is based on their models of radiological movement at the site. In response, the Colorado public is outraged. Rather than models, locals of Rulison base their knowledge on experience—experience with escaped gases from wells incorrectly drilled or managed, discovery of radioactive debris left by Plowshare contractors who were supposed to have sent it to the rad-waste dump in Nevada but instead surreptitiously buried it in the farmstead next door to the test site, and the fact that the models the DOE uses are 30 years old. Locals complain that there is no public participation, and they claim that the DOE doesn’t adequately test the soil and tests the water only superficially, and more. At the end of U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management, "Final Rulison Path Forward," LMS/RUL/S04617, June 2010, https://lmpublicsearch.lm.doe.gov/lmsites/2346-s04617_pf.pdf. Also see: U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management, “Path Forward for Gas Drilling near the Rulison, Colorado, Site Revision 1,” LMS/RUL/S04617, December 2019, https://lmpublicsearch.lm.doe.gov/lmsites/2404-s04617_rul_pathforward.pdf.Legacy Management’s report “Final Rulison Path Forward,” there is a final section that allows the people of the region to respond to what the DOE and the Office of Legacy Management say about the tests, the remaining levels of radiation in the surrounding environment, remediation of the site, and the ongoing monitoring of Rulison and Rio Blanco. The first response is by a representative from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) who states:

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management, "Final Rulison Path Forward," LMS/RUL/S04617, June 2010, https://lmpublicsearch.lm.doe.gov/lmsites/2346-s04617_pf.pdf.“CDPHE does not believe DOE has gathered, evaluated, or presented sufficient actual data to adequately characterize the Rulison blast site and thus is unable to determine where it is safe to develop oil and gas resources within a half mile of the blast site.”

Conclusion

All of this, including the blatant disregard for radiation exhibited by the weaponeers and their industrial consorts, makes one wonder what exactly these tests were really all about. The demonstrations of Atoms for Peace in Colorado, which were supposed to make people feel good about the nuclear weapons complex, failed on many levels—not just because the radioactive gas couldn’t be sold by the industry. Rather than making people see the nuclear weapons complex as a good and benevolent program, it has made people in Colorado angry enough to protest and create alliances against programs like nuclear stimulated gas. The Plowshare tests in Colorado had the effect of making Colorado the first state to pass legislation making it illegal for anyone to detonate a nuclear device in Colorado ever again—at least not without a full vote by all citizens of the state.

Kelly Michals, Project Rio Blanco well, 7 April 2012, Flickr

The two Colorado sites, Rulison and Rio Blanco, were the final experiments of the Plowshare program before it ended. None of the Plowshare experiments proved cost effective compared to conventional earth moving or oil and gas stimulation techniques, and funding effectively dried up. Even from the very beginning, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) faced intense local and state opposition with the American Civil Liberties Union, the Colorado Open Space Coordinating Council, and a private citizen, M.G. Dumond; they filed lawsuits to prevent the detonation of Project Rulison, and citizen groups actively protested the AEC’s dangerous and radioactive experiments on private and public lands for potentially exposing local inhabitants to radiation contamination. Because of its economic failure and because of the litigation and court costs from the citizens of Colorado, the AEC decided to pull out of the Plowshare program altogether after the tests were over.

With its mandate to find peaceful alternatives to weapons of mass destruction, the Atoms for Peace program ended in failure on Colorado’s ruggedly beautiful Western Slope, leaving behind two small markers identifying the sites where nuclear tests were conducted at Rulison and Rio Blanco. In these two regions deep in shale country, where the earth is laced with radionuclides, frackers now descend upon ground zero in search of artificially enhanced reservoirs of shale-oil.

Contamination comes with the territory of splitting atoms—no matter what one does with it. Colorado’s test sites can be recognized as the continuation of a delusional ethos of control that has always been at the core of the nuclear complex, an ethos that feeds on and legitimates projects responsible for the evaporation of whole atolls (the thermonuclear bomb, such as Bravo), the creation of a vast waste stream of unthinkable dimensions and toxicity, and the contemporary practices known as fracking that have resurfaced around these abandoned experimental domains. The belief that Rio Blanco could be reconstructed from a living earth into a fused and perpetually hot cauldron—or retort—for the collection and retention of usable gas, or that Rulison could be fracked with nuclear weapons for the profit of global oil and gas markets, is founded upon a desire for profit and power, not peace. Such practices have continued into the present with advanced “conventional” hydrofracking techniques, and the nuclear labs have continued to experiment with oil and gas companies in search of new technologies more destructive than in the past. In this way the past is rekindled—literally—as once again private and government interests collude, illuminating the linkages between globalizing private corporate concerns with U.S. global weapons brokers. Atoms for War cannot be made into Atoms for Peace.

Sources

CER Geonuclear. “Project Rio Blanco Final Report Detonation Related Activities.” June 30, 1975. Accessed July 26, 2020.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. “Atoms for Peace.” December 8, 1953. United Nations General Assembly. Accessed July 26, 2020.

Eisenhower, Dwight D. “'Atoms for Peace' Speech." International Atomic Energy Agency website. Accessed July 26, 2020.

London, Nell. “Drilling Near the Site of an Underground Nuclear Blast Just Got a Little Easier.” Colorado Public Radio, November 6, 2017. Accessed July 26, 2020.

Project Rulison Joint Office of Information, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Austral Oil Company, Inc., U.S. Department of Interior, and CER Geonuclear Corporation. “Project Rulison: A Government-Industry Natural Gas Production Stimulation Experiment Using a Nuclear Explosive.” May 1, 1969. Accessed July 26, 2020.

Tewes, H.A. “Survey of Gas Quality Results from Three Gas-well-stimulation Experiments by Nuclear Explosions.” OSTI.gov / U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Scientific and Technical Information. 1979. Accessed July 26, 2020.

“The Atom: Underground.” Part of the “Magic of the Atom” series, with footage from the Atomic Energy Commission. Periscope Film LLC archive. PeriscopeFilm. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. "Final Rulison Path Forward." LMS/RUL/S04617. June 2010. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. “FUSRAP Considered Sites: Project Rio Blanco (CO.0-09).” Energy.gov, December 16, 2015 [last update]. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. "Geospatial Environmental Mapping System: Rio Blanco." Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. "Geospatial Environmental Mapping System: Rulison." Accessed July 26, 2020.

.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. “Path Forward for Gas Drilling near the Rulison, Colorado, Site Revision 1.” LMS/RUL/S04617. December 2019. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. “Rio Blanco, Colorado, Site.” Energy.gov. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. “Rio Blanco, Colorado, Site” Fact Sheet. November 2018. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Legacy Management. “Rulison, Colorado, Site.” Energy.gov. Accessed July 26, 2020.

U.S. Department of Energy, “Project Rulison 1969.” Video 0800036 ClassicAtomicMovies. Accessed July 26, 2020.